The Best Practices, however, are not new evaluative criteria. Rather they explicate how the well-established essentials of institutional quality found in regional accreditation standards are applicable to the emergent forms of learning; much of the detail of their content would find application in any learning environment. Taken together those essentials reflect the values which the regional commissions foster among their affiliated colleges and universities:

- that education is best experienced within a community of learning where competent professionals are actively and cooperatively involved with creating, providing, and improving the instructional program;

- that learning is dynamic and interactive, regardless of the setting in which it occurs;

- that instructional programs leading to degrees having integrity are organized around substantive and coherent curricula which define expected learning outcomes;

- that institutions accept the obligation to address student needs related to, and to provide the resources necessary for, their academic success;

- that institutions are responsible for the education provided in their name;

- that institutions undertake the assessment and improvement of their quality, giving particular emphasis to student learning and voluntarily subject themselves to Periodic Review

Ten Principles for Effective Online Teaching [pdf]

Best Practices in Online Teaching: Guidepost for the Instructor [pdf]

Best Practice for Online Teaching 2014 Summer Institute Guide [pdf]

An online course does not “teach itself.” This idea is generated by the fact that most institutions require their courses to be fully developed and ready to go on the first day of class. In reality, the instructor is far more important than a troubleshooter waiting in the background of the course.

Students look for and expect to find three distinct personalities: teacher, guide, and facilitator.

Show up and teach translates as such … with the course designed and developed, more time can now be spent interacting with the students around the course learning objectives. This is especially true when you take in account the free time gained by no longer being required to prepare for the next classroom encounter (lecture and handouts, etc.).

In short, you can spend that time responding to questions, helping with difficult subject matter, discussing current events that are relevant to your content, and assessing student growth. It really is an efficiency. It is also the instructor’s responsibility to be familiar with the institution’s learning management system (LMS) and to help students navigate their course. Being competent with the LMS provides the online instructor several advantages:

- Their students view them as competent with the learning management system.

- Their students view them as competent with the course they are teaching and responsible for.

- Their students have more “up-time” to complete course work and stay on track.

- Instructors do not have to contact support and request for assistance and wait for a response, which translates to lower frustration levels and more up-time for everyone in the class.

The online course runs as well as it is designed and managed. Being the teacher, guide, and facilitator requires your presence, time, and communication. Your course is not self-taught … show up and teach.

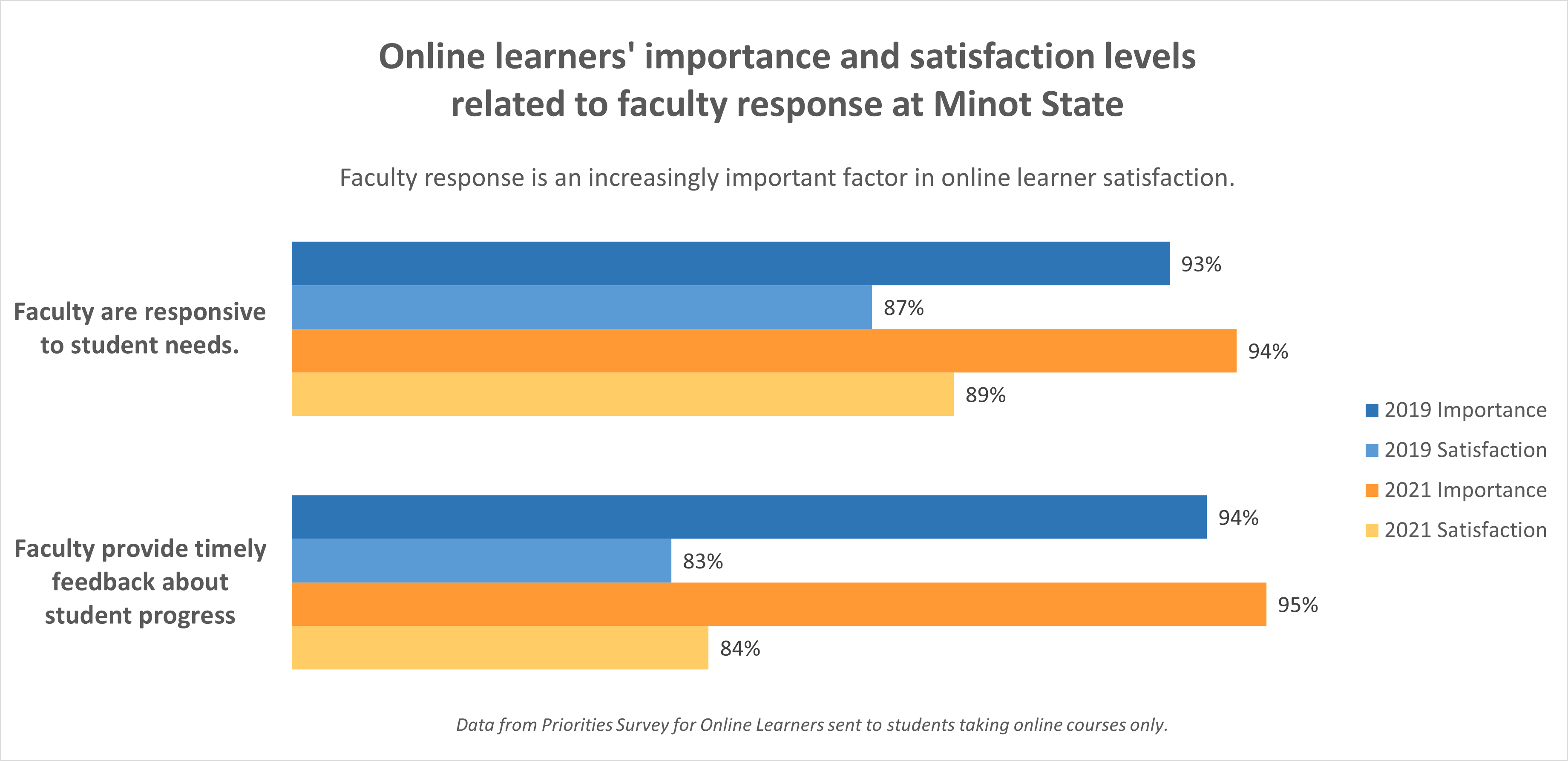

Communication is essential to the successful operation and management of an online course. For the student, it is essential for mastery of the course learning objectives and completion of the course. Online students also rate faculty response as very important in their expectation of an online course or program.

Students of the twenty-first century have different expectations of the communications and technologies they use for work and play. Most have come to count on timely, if not, immediate response. They become quickly annoyed with a web site or video that loads slowly, or worse, fails to load. They quickly become frustrated when a colleague or peer fails to response within a business day. And it is a fact, that we all have developed some level of similar expectation. It has become the norm.

A delay in an online course, whether it be with the technology or a response from the instructor or a peer in the classroom compounds the issues for the student, because it delays, if not in some cases, stops the forward momentum in the course. Remember:

- The distant student can’t just drop by your office and in some cases (time zones), calling isn't even a simple solution.

- The distant student is trying to meet your deadlines, time delays often result in those deadlines not being met.

Timely response is critical to everyone involved in the course. But then, what is timely?

Timely is hard to define because it involves several variables. You may respond immediately to every inquiry you encounter, but what it you only check your course twice a week? As you can imagine, this scenario will not work. First, consider the duration of your course; is it a 16-week course, or a ten or eight-week course? It should be understood that a short duration course is going to require more frequent exposure to the course and communication with the students.

Then you have to consider the nature of the course work, course load, types of assignments, and the level of the students being engaged. Industry standards suggest a business day as the norm, 24-hours during the work week and 48-hours over the weekend. This also needs to be clearly defined in the syllabus and not just for the instructor, but also for your expectation for the student responses.

Once defined and communicated, a rhythm of communication can be created and expectations enjoyed, not frustrated. When both sides meet expectations, another benefit emerges— students see the instructor attending to their needs, and present and engaged.

However, there are times when the “defined” expectation may be inadequate. Examples include:

- When questions or problems arise immediately before high stake exams, assignments, or projects

- When students appear confused over course details or instructions

- When students appear confused or do not understand course material

- When you as the instructor determine additional content or feedback is essential to student success

And we are certain you can think of other examples. Response time can be 24- hours in the syllabus, but remember the solution does not fit all situations. The standard you set in the syllabus will for the most part allow students to plan their learning experience. It will also remove the myth of 24/7 access to the instructor. Your commitment to the standard, mixed with flexibility, will help students respect your need to balance the course with your other teaching obligations and home life.

There are three levels of interaction in the online course.

- Student to content

- Student to student

- Student to instructor

A quality course will have evidence of all three levels of interaction across the design. These can include discussions, web-conferencing events, instructor-based recordings (audio and/or video), online office hours, blogs, wikis, group projects and/or presentations. Interaction involves contact and collaboration between participants. It is an exchange of information and communication that are high risk and of high value, content (learning objective) focused, and involves instructor participation and feedback across the exercise.

During the initial Beta Test and subsequent Four-Year Periodic Review we look for examples of each. But each course should contain at least one major interaction that involves all three levels. While some instructors provide quantitative requirements to these major exercises, such as a discussion project that requires students to “read five peer responses” and “respond to three peer posts,” we recommend qualitative standards through the use of rubrics and/or specific learning objectives.

Interaction addresses boredom, enhances the learning environment, and speaks to learner preferences for the modality, increases retention, and student success. More importantly, interaction in the course leads to a more concrete learning community, trust, and the development of formal classroom relationships that are critical to the distant student’s success.

The Higher Learning Commission provide Higher Education two critical definitions: Distance Education and Correspondence Education (Italics added). Please become familiar with the distinct differences between these two delivery methods.

Distance Education: Education that uses one or more of the technologies listed below to deliver instruction to students who are separated from the instructor and to support regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor, either synchronously or asynchronously. The technologies may include:

- The Internet.

- One-way and two-way transmissions through open broadcast, closed circuit, cable, microwave, broadband lines, fiber optics, satellite or wireless communications devices.

- Audio conferencing.

- Video cassettes, DVDs and CD-ROMs, if the cassettes, DVDs or CD-ROMs are used in a course in conjunction with any of the technologies listed above.

Correspondence Education: Education provided through one or more courses by an institution under which the institution provides instructional materials by mail or electronic transmission, including examinations on the materials, to students who are separated from the instructor.

Interaction between the instructor and the student is limited, is not regular and substantive, and is primarily initiated by the student. Correspondence courses are typically self-paced. Correspondence education is not distance education. Correspondence does NOT qualify for financial aid.

While your course may be marketed as asynchronous, it is highly encouraged to offer some option for synchronous activity. This may simply be office hours or perhaps a brief overview before a high stakes mid-term or final, or even the use of optional web conferencing for group projects or presentations.

It’s simple … it is hard to replace the opportunity for groups to talk real time and brainstorm, coordinate activities, and collaborate on design of documents or presentations. The sessions can be archived, so you can watch them later and see who is doing what and when. Giving this option to your students empowers them and provides them the tools for a successful project.

Office hours gives students the opportunity to engage the ‘physical’ you in contrast to the ‘virtual” version. It makes the connection more real and develops a sense of place, security, and sorry, but reality for the learner. E-learning can often result in isolation for the learner, when in fact they should be connected to an active online community that has much to co-teach and share.

However, it is important to remember that according to the definition of an online asynchronous course, synchronous activities must be optional for students and arranged to accommodate all students’ schedules or alternative options offered.